Human Depopulation May Lead to Biodiversity Loss

Findings from a Big Data Analysis of 158 Satoyama and Rural Areas Across Japan

2025.6.13

Figure 1. Landscape of a Satoyama Area, Oyama Senmaida. Photo by Nobuko Ushimura.

Associate Professor Kei Uchida of the Faculty of Environmental Studies at Tokyo City University, Senior Lecturer Peter Matanle and Postdoctoral Researcher Dr. Yang Li of the University of Sheffield, Team Leader Taku Fujita of the Nature Conservation Society of Japan (NACS-J), and Dr. Masayoshi Hiraiwa (then a postdoctoral researcher at Kindai University’s Faculty of Agriculture, now a research associate at Kindai University) formed a research team to examine the impacts—both beneficial and detrimental—of human depopulation on aspects of biodiversity* in Japan.

Their findings revealed that human depopulation may contribute to biodiversity loss in Japan’s satoyama and rural landscapes**. The impact of human population increase, on the other hand, varied depending on the taxonomic group, with bird species particularly showing significant declines. These findings are expected to help spread a shared understanding—particularly in East Asia and Western countries, where human depopulation is advancing—that biodiversity can also be lost as a result of depopulation. As achieving a nature-positive society becomes a global goal, it is crucial to understand that biodiversity does not automatically recover as human populations decrease. In fact, certain forms of biodiversity may be lost precisely because of depopulation, and future ecosystem conservation efforts must be planned and implemented with this perspective in mind.

These research findings were published online in Nature Sustainability on June 12, 2025 (U.S. Eastern Time).

Contents

Key points of the Study

- The study analyzed medium- to long-term changes (5 to 17 years) in species richness and abundance for more than 450 species of birds, butterflies, fireflies, and frog egg masses, as well as approximately 3,000 species of plants, using data from the “Monitoring Sites 1000 SATOYAMA Survey”*** conducted across 158 satoyama and rural areas throughout Japan. These biodiversity changes were examined in relation to changes in human population and land use.

- The results revealed that human depopulation may contribute to biodiversity loss in Japan’s satoyama landscapes, and that the impact of human population increase varies depending on the taxonomic group.

- The hypothesis that human depopulation would automatically lead to biodiversity recovery was not supported in Japanese satoyama areas. The study underscores the importance of taking human population changes into account when countries around the world—many of which are facing either depopulation or population growth—develop strategies for biodiversity conservation and restoration.

Outline

A research group comprising Tokyo City University, the University of Sheffield (UK), the Nature Conservation Society of Japan (NACS-J), and Kindai University conducted a study investigating the potential benefits of population change on biodiversity. Their findings showed that biodiversity—including birds, frogs (Rana japonica, Rana ornativentris, and Rana pirica), insects (butterflies and both Genji-botaru and Heike-botaru fireflies), and plants—was often declining in both regions experiencing human population increase and those undergoing the population decline. The study demonstrated that human depopulation would automatically lead to biodiversity recovery and “rewilding” (restoration of ecosystems with no human influence) does not apply to Japan’s satoyama and rural landscapes.

The global ecosystem is facing a crisis. Since 1970, 73% of the world’s wildlife has been lost, while the human population has doubled, now exceeding 8 billion. Numerous studies have shown a direct link between human population and economic growth and the loss of habitats and species. Amid this global concern, human depopulation has already begun in developed countries. There is growing hope that this decline might bring about a "depopulation dividend"—a recovery of ecosystems as human pressures lessen. While population growth continues to threaten biodiversity hotspots worldwide, Japan faces the opposite trend: a declining population. However, until now, few studies have conducted detailed analyses of how spatial and temporal changes in population affect biodiversity.

This study integrated large-scale biodiversity and demographic datasets within Japan, analyzing biodiversity changes (species richness and population abundance) in relation to regional population trends, land use, and surface temperature fluctuations. It revealed patterns of biodiversity gain and loss at 158 sites across the country. These sites span Japan’s satoyama landscapes, located between steep forested mountains, coastal zones, and urban centers. They include farmland, orchards, grasslands, ponds, waterways, secondary and planted forests, satoyama, and towns and villages.

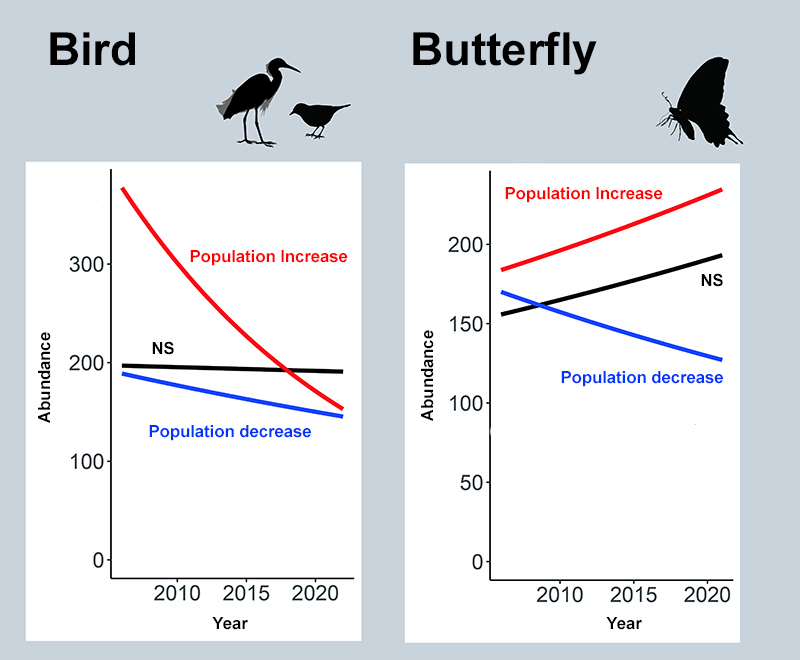

The findings show that, at present, human depopulation in Japan is not automatically leading to increases in species richness or abundance. This trend was particularly notable in birds and butterflies (see Figures 2 and 3). In contrast, in areas experiencing population growth, the impact on biodiversity varied by taxonomic group: while bird populations declined significantly, butterfly populations tended to increase (see Figure 3). In short, human depopulation does not immediately restore human-altered lands into ecosystems suitable for wildlife. In Japan, even depopulated areas continue to undergo development, and "gray infrastructure"—environments unsuitable for wildlife—is still on the rise.

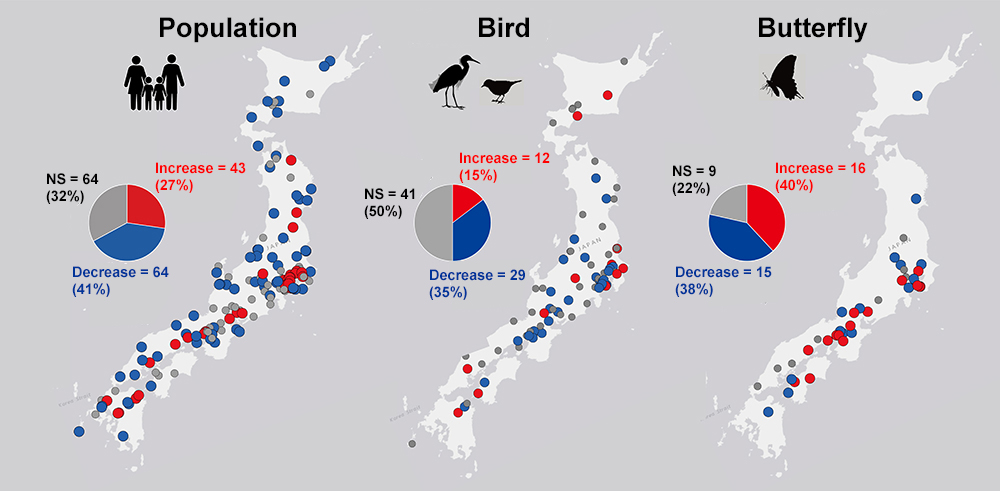

Figure 2. Changes in Human Population and Biodiversity (DOI: 10.1038/s41893-025-01578-w)

(Human population change is based on data from 1995 to 2020; changes in bird and butterfly populations are based on data from 2004 to 2022 (timeframes vary by site). Increases, no change, or decreases were determined based on statistical analysis.)

Figure 3. Relationship Between Human Population Change and Biodiversity (DOI: 10.1038/s41893-025-01578-w)

One of the four major threats to biodiversity in Japan is the abandonment of management in satoyama and rural areas. This abandonment is driven by human depopulation and the loss of those responsible for maintaining traditional land-use practices. Until now, few studies have quantitatively demonstrated the impact of this on biodiversity at a national scale. This study is the first to show that human depopulation—which significantly contributes to the abandonment of land management—may lead to biodiversity loss in satoyama areas, particularly among birds and butterflies.

These results are not entirely surprising and are likely attributable to the shrinking of habitats due to the decline or disappearance of traditional livelihoods such as farming, soil and forest management, and landscape maintenance. Additionally, even in depopulated areas, artificial development continues. In many unmanaged regions, grasslands and farmlands are undergoing ecological succession and becoming forested, further reducing satoyama environments. According to the latest demographic data, all 47 prefectures in Japan are experiencing low birth rates, population aging, and human depopulation. In many areas, urban land use is still expanding, agricultural lands are being abandoned or consolidated, and some regions are becoming increasingly forested due to plantation forestry or succession.

The study’s findings suggest that human depopulation and associated land-use changes could lead to biodiversity loss not only in Japan but also in similar rice-farming landscapes across East Asia, including China, South Korea, and Taiwan. The results warn that simply waiting for spontaneous ecological recovery in the face of human depopulation is likely to produce disappointing outcomes.

However, human depopulation also presents an important opportunity to propose and implement solutions for social and environmental regeneration. In satoyama landscapes in particular, the continuation of traditional land management practices is essential to maintaining biodiversity. To realize the potential biodiversity benefits of depopulation, it is vital to monitor long-term relationships between human activity and the environment and to implement active management strategies.

Research Background

The global ecosystem is in a critical state. Since 1970, 73% of the world’s wildlife has been lost, while the human population has reached 8 billion. During this same period, the global economy—particularly in wealthy countries—has grown by 3,415%. Habitat and species loss are directly linked to human population growth and economic expansion, and there are growing concerns that Earth may be entering a sixth mass extinction.

The Earth's sustainable population is estimated to be between 3.1 and 3.3 billion people, a threshold that was already exceeded by 1965. Since then, global birth rates have declined, raising hopes for potential environmental recovery. However, the impacts of human depopulation on ecosystems remain under-researched, and debate continues over whether depopulation will promote ecological restoration or, conversely, exacerbate biodiversity loss.

According to United Nations projections, by 2050, 85 countries will be experiencing human depopulation, and in 73 countries, the population is expected to decrease by more than 1% compared to 2023. Japan and Italy are seen as early examples of this trend. In particular, Japan has been experiencing continuous human depopulation since 1995, making it a valuable case study for understanding how demographic shifts interact with environmental change and informing research in other countries.

This study utilized biodiversity data collected through the Monitoring Sites 1000 – SATOYAMA Survey, a monitoring project implemented by the Ministry of the Environment in collaboration with the Nature Conservation Society of Japan (NACS-J). The data was gathered with the cooperation of over 5,700 field surveyors across Japan.

According to United Nations projections, 85 countries are expected to experience continued human depopulation by 2050. The findings of this study from Japan may offer valuable insights not only for East Asia but also for other regions facing similar demographic trends. Moving forward, it will be important to expand the geographic scope of such research to include Western countries where human depopulation is projected, in order to investigate changes in biodiversity.

In line with the global biodiversity goal set by the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which aims to halt biodiversity loss and put nature on a path to recovery by 2030, and to realize a nature-positive world in harmony with nature by 2050, countries around the world will need to develop and implement biodiversity conservation and restoration strategies that explicitly take into account the impacts of population change.

Reference

Published Article Information

Title: Biodiversity Change under Human Depopulation in Japan

Authors: Kei Uchida, Peter Matanle, Yang Li, Taku Fujita, and Masayoshi K. Hiraiwa

Journal: Nature Sustainability

DOI: 10.1038/s41893-025-01578-w

Online Access: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-025-01578-w

Research Introduction Video (25 seconds)

YouTube URL: https://youtube.com/shorts/86fguzoTp7Y?feature=share

BGM from the band "MayDays in Barcelona" based on Sheffield

Glossary

*Biodiversity:

A broad concept that encompasses the richness of living things. It includes not only biological resources such as food and medicine, but also plays a crucial role as the foundation for human survival. However, with the expansion of human activities, biodiversity is in decline and is now recognized as one of the major global environmental issues.

**Satochi and Satoyama:

These are areas located between pristine natural environments and urban zones. These typically consist of rural settlements and the surrounding managed secondary forests, agricultural fields, irrigation ponds, and grasslands.

***Monitoring Sites 1000 – SATOYAMA Survey:

"Monitoring Sites 1000" is a long-term ecological monitoring project launched by Japan’s Ministry of the Environment in 2003. It aims to monitor the dynamics of Japan’s representative ecosystems (alpine zones, forests and grasslands, satoyama, lakes and wetlands, coastal areas, small islands, etc.) at approximately 1,000 locations nationwide for over 100 years, and to apply the findings to biodiversity conservation policies.

The Satochi Survey component of this project focused on satoyama areas and was conducted from fiscal year 2008 to 2022. Surveys were carried out at 325 sites across Japan with the cooperation of approximately 5,700 citizen scientists, covering nine categories including plants, birds, and butterflies.

Co-researchers

![]()

Kei Uchida

Faculty of Environmental Studies, Tokyo City University, Yokohama, Japan.

Peter Matanle

School of East Asian Studies, University of Sheffield, UK.

Yang Li

School of East Asian Studies, University of Sheffield, UK.

Taku Fujita

The Nature Conservation Society of Japan, Tokyo, Japan.

![]()

Masayoshi K. Hiraiwa

Faculty of Agriculture, Kindai University, Nara, Japan.

Latest List

2025.12.19

Nature Positive initiative launched in Nose Town, Osaka

with support from Microsoft

In collaboration with the Foundation of Osaka Green Trust and local communities

2025.5.21

Collaboration with Panasonic!

Purchasing a Panasonic hair dryer can contribute to plastic reduction and nature conservation!

2025.5.20